Introduction

Cluster analysis (or clustering) attempts to group observations into clusters so that the observations within a cluster are similar to each other while different from those in other clusters. It is often used when dealing with the question of discovering structure in data where no known group labels exist or when there might be some question about whether the data contain groups that correspond to a measured grouping variable. Therefore, cluster analysis is considered a type of unsupervised learning. It is used in many fields including statistics, machine learning, and image analysis, to name just a few. For a general introduction to cluster analysis, see Everitt and Hothorn (2011, Chapter 6).

Commonly used clustering methods are \(k\)-means (MacQueen, 1967) and Ward’s hierarchical clustering (Murtagh and Legendre, 2014; Ward, 1963), which are both implemented in functions kmeans and hclust, respectively, in the stats package in R (R Core Team, 2019). They belong to a group of methods called polythetic clustering (MacNaughton-Smith et al., 1964) which use combined information of variables to partition data and generate groups of observations that are similar on average. Monothetic cluster analysis (Chavent, 1998; Piccarreta and Billari, 2007; Sneath and Sokal, 1973), on the other hand, is a clustering algorithm that provides a hierarchical, recursive partitioning of multivariate responses based on binary decision rules that are built from individual response variables. It creates clusters that contain shared characteristics that are defined by these rules.

Given a clustering algorithm, the cluster analysis is heavily influenced by the choice of \(K\), the number of clusters. If \(K\) is too small, it puts “different” observations together. On the other hand, if \(K\) is too large, the algorithm might split observations into different clusters that share many characteristics or are similar. Therefore, picking a sufficient, or “correct”, \(K\) is critical for any clustering algorithm. A survey of some techniques for estimating the number of clusters has been done by Milligan and Cooper (1985). The R package NbClust (Charrad et al., 2014) is dedicated to implementations of those techniques. However, none of them were designed to work with monothetic clustering or take advantage of its unique characteristics, where binary splits generate rules for predicting new observations and each split is essentially a decision about whether to continue growing the tree or not. \(M\)-fold cross-validation (a brief introduction can be seen in Hastie et al., 2016) and permutation-based hypothesis test at each split similar to those in Hothorn et al. (2006) are the two techniques that have been shown to work well in the classification and regression tree setting and we have adapted them to work with monothetic clustering.

Clustering data sets including circular variables, a type of variables measured in angles indicating the directions of an object or event (Fisher, 1993; Jammalamadaka and SenGupta, 2001) requires a different sets of statistical methods from conventional “linear” quantitative variables. An implementation of monothetic clustering modified to work on circular variables is discussed here. To assist in visualizing the resulting clusters and interpreting the shared features of clusters, a visualization of the results based on parallel coordinates plots (Inselberg and Dimsdale, 1987) are also implemented in the monoClust package. The package has been applied to the particle counts in föhn winds in Antarctica (wind_sensit_2007 and wind_sensit_2008 data sets from Šabacká et al., 2012).

Monothetic Clustering

Let \(y_{iq}\) be the \(i^\mathrm{th}\) observation (\(i = 1, \ldots, n\), the number of observations or sample size) on variable \(q\) (\(q = 1, \ldots, Q\), the number of response variables) in a data set. In cluster analysis, \(Q\) variables are considered “response” variables and the interest is in exploring potential groups in these responses. Occasionally other information in the data set is withheld from clustering to be able to understand clusters found based on the \(Q\) variables used in clustering. Clustering algorithms then attempt to partition the \(n\) observations into mutually exclusive clusters \(C_1, C_2, \ldots, C_K\) in \(\Omega\) where \(K\) is the number of clusters, so that the observations within a cluster are “close” to each other and “far away” from those in other clusters.

Inspired by regression trees (Breiman et al., 1984) and the rpart package (Therneau and Atkinson, 2018), the monothetic clustering algorithm searches for splits from each response variable that provide the best split of the multivariate responses in terms of a global criterion called inertia. To run successfully on a data set, the MonoClust function of the monoClust package only has one required argument, which is the data set name in the toclust option. By default, MonoClust will be performed by first calculating the squared Euclidean distance matrix between observations. The calculation of the distance matrix is very important to the algorithm because inertia, a within-cluster measure of variability when Euclidean distance is used, is calculated by \begin{equation} I(C_k) =\sum_{i \in C_k} d^2_{euc}(\mathbf{y_i}, \overline{y}_{C_k}), \end{equation} where \(\overline{y}_{C_k}\) is the mean of all observations in cluster \(C_k\). This formula has been proved to be equivalent to the scaled sum of squared Euclidean distances among all observations in a cluster (James et al., 2013, p 388), \begin{equation} I(C_k) = \frac{1}{n_k} \sum_{(i, j) \in C_k, i > j} d^2_{euc}(\mathbf{y_i},\mathbf{y_j}). \end{equation}

A binary split, \(s(C_k)\), on a cluster \(C_k\) divides its observations into two smaller clusters \(C_{kL}\) and \(C_{kR}\). The inertia decrease between before and after the partition is defined as \begin{equation} \Delta (s, C_k) = I(C_k) - I(C_{kL}) - I(C_{kR}), \end{equation} and the best split, \(s^*(C_k)\), is the split that maximizes this decrease in inertia, \begin{equation} s^*(C_k) = \arg \max_s \Delta(s, C_k). \end{equation} The same algorithm is then recursively applied to each sub-partition, recording splitting rules on its way until it reaches the stopping criteria, which can be set in MonoClust by at least one of these arguments:

-

nclusters: the pre-defined number of resulting clusters; -

minsplit: the minimum number of observations that must exist in a node in order for a split to be attempted (default is 5); -

minbucket: the minimum number of observations allowed in a terminal leaf (default isminsplit/3).

As a very simple example, monothetic clustering of the ruspini data set (Ruspini, 1970) available in the cluster package (Maechler et al., 2018) with 4 clusters can be performed as follows:

library(monoClust)

library(cluster)

data(ruspini)

ruspini4c <- MonoClust(ruspini, nclusters = 4)

ruspini4c

#> n = 75

#>

#> Node) Split, N, Cluster Inertia, Proportion Inertia Explained,

#> * denotes terminal node

#>

#> 1) root 75 244373.900 0.6344215

#> 2) y < 91 35 43328.460 0.9472896

#> 4) x < 37 20 3689.500 *

#> 5) x >= 37 15 1456.533 *

#> 3) y >= 91 40 46009.380 0.7910436

#> 6) x < 63.5 23 3176.783 *

#> 7) x >= 63.5 17 4558.235 *

#>

#> Note: One or more of the splits chosen had an alternative split that reduced inertia by the same amount. See "alt" column of "frame" object for details.The output (print.MonoClust) lists each split on one line together with the splitting rule as well as its inertia and is displayed with the hierarchical structure so the parent–child relationships between nodes can be easily seen. This function defines a MonoClust object to store the cluster solution with some useful components:

-

frame: a partitioning tracking table in the form of adata.frame; -

membership: a vector of numerical cluster identification (incremented by new nodes) that observations belong to; and -

medoids: the observation indices that are considered as representatives for the clusters (Kaufman and Rousseeuw, 1990), estimated as the observations that have minimum total distance to all observations in their clusters.

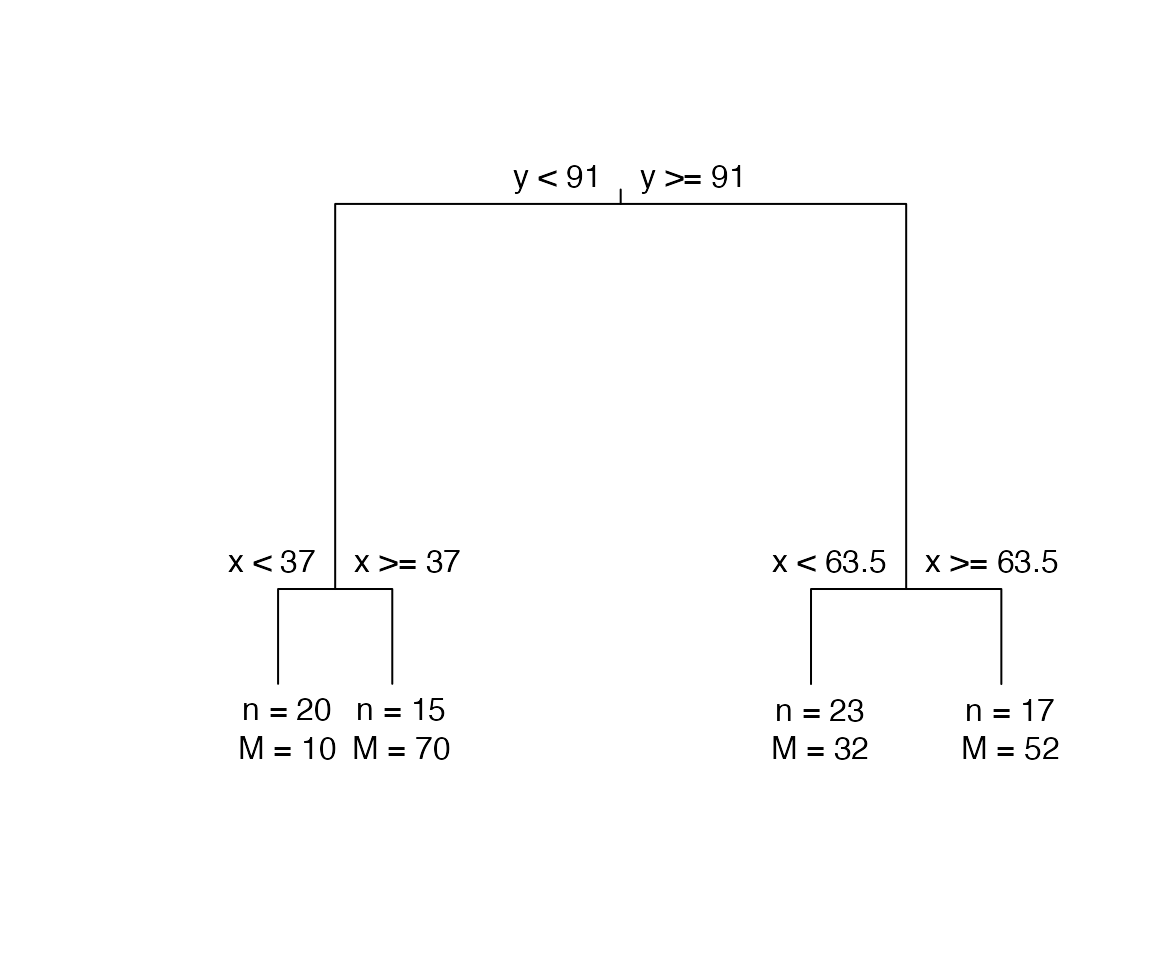

Another visualization of the clustering results is the splitting rule tree created by the plot.MonoClust function of the MonoClust object.

plot(ruspini4c)

Binary partitioning tree with three splits, four clusters for ruspini data.

The initial development of MonoClust was based on rpart. However, we steered away to develop our own algorithms to significantly enhance the structure to implement the various methods.

Testing at Each Split to Decide the Number of Clusters

Deciding on the number of clusters to report and interpret is an important part of cluster analysis. Among many metrics mentioned in Milligan and Cooper (1985) and Hardy (1996), Caliński and Harabasz (CH)’s pseudo-\(F\) (Caliński and Harabasz, 1974) is among the metrics that have typically good or even the best performance in the Milligan and Cooper (1985)’s simulation studies on selecting the optimal number of clusters. Additionally, average silhouette width (AW), a measure of how “comfortable” observations are in their clusters they reside in, has also been suggested to select an appropriate number of clusters (Rousseeuw, 1987). One limitation of both criteria is that they are unable to select a single cluster solution because their formula require at least two clusters to calculate the criteria. We have proposed two methods that can assist select the number of clusters in monothetic clustering. One is inspired by regression tree methods for pruning regression and classification trees, which is an adaption of \(M\)-fold cross-validation technique. Another one is inspired by conditional inference trees (Hothorn et al., 2006). It is a formal hypothesis test at a split to determine if it should be performed using two different test statistics. Finally, we suggested a hybrid method that uses the hypothesis test with CH’s \(F\) statistic at the first split and then uses the original CH’s \(F\) for the further splits if the test suggests that there should be at least two clusters.

The \(M\)-fold cross-validation randomly partitions data into \(M\) subsets with equal (or close to equal) sizes. \(M - 1\) subsets are used as the training data set to create a tree with a desired number of leaves and the other subset is used as validation data set to evaluate the predictive performance of the trained tree. The process repeats for each subset as the validating set (\(m = 1, \ldots, M\)) and the mean squared difference, \begin{equation} MSE_m=\frac{1}{n_m} \sum_{q=1}^Q\sum_{i \in m} d^2_{euc}(y_{iq}, \hat{y}_{(-i)q}), \end{equation} is calculated, where \(\hat{y}_{(-i)q}\) is the cluster mean on the variable \(q\) of the cluster created by the training data where the observed value, \(y_{iq}\), of the validation data set will fall into, and \(d^2_{euc}(y_{iq}, \hat{y}_{(-i)q})\) is the squared Euclidean distance (dissimilarity) between two observations at variable \(q\). This process is repeated for the \(M\) subsets of the data set and the average of these test errors is the cross-validation-based estimate of the mean squared error of predicting a new observation, \begin{equation} CV_K = \overline{MSE} = \frac{1}{M} \sum_{m=1}^M MSE_m. \end{equation}

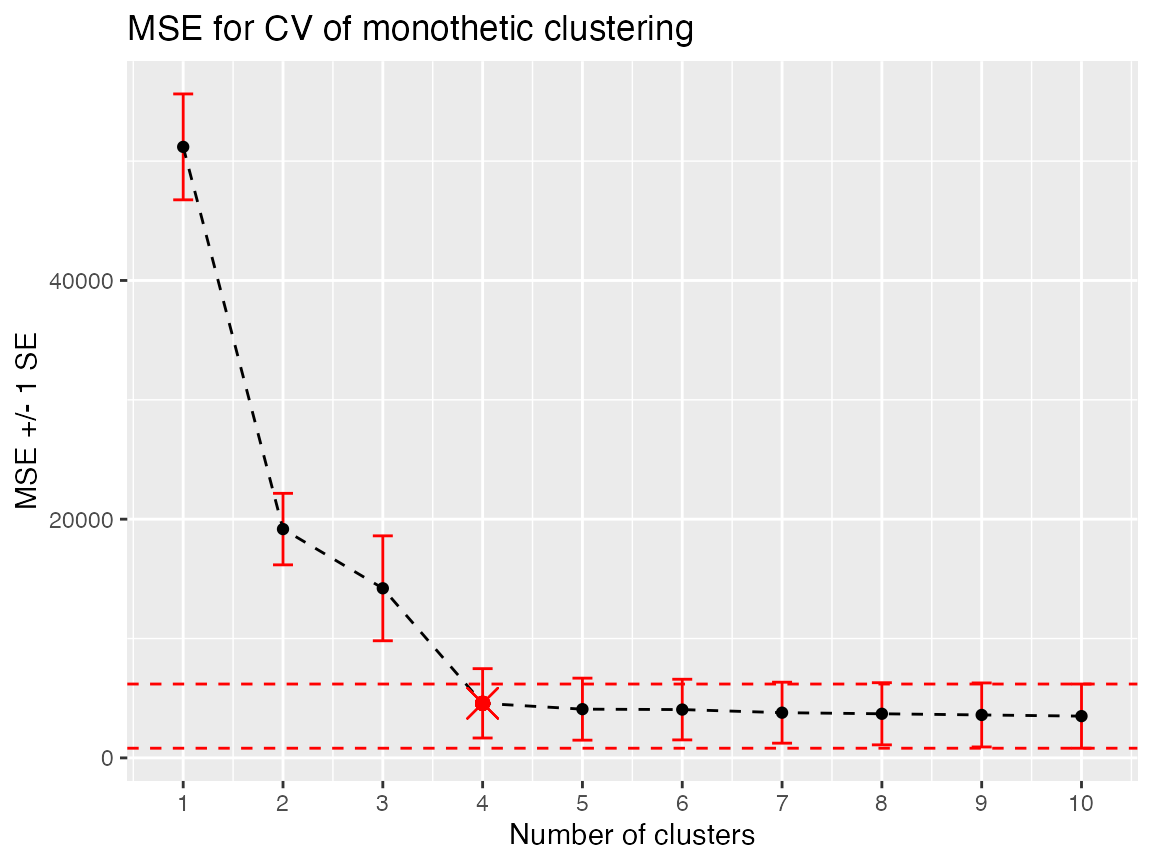

The purpose of the cross-validation is to find a cluster solution that achieves the “best” prediction error for new observations. There are several ways one can decide from the output of MonoClust. A naive approach is to pick the solution that has the smallest \(CV_K\) (minCV rule). However, in many cases, it can result in a very high number of clusters if the error rate keeps decreasing even though there is often a small change after a few large drops. To avoid this problem, Breiman et al. (1984) suggested picking the solution that is simplest within 1 or 2 standard errors (SE) from the minimum error estimate (CV1SE or CV2SE rules), with the standard error is defined as \[SE(\overline{MSE}) = \sqrt{\frac{1}{M} \sum_{m=1}^M (MSE_m - \overline{MSE})}.\] The function cv.test with the data set and two arguments minnodes and maxnodes defining the range of nodes to test on will apply MonoClust and calculate both \(\overline{MSE}\) (which is named MSE in the output) and its standard error (named Std. Dev.).

set.seed(12345)

cp.table <- cv.test(ruspini, fold = 5, minnodes = 1, maxnodes = 10)

cp.table

#> 5-fold Cross-validation on a MonoClust object

#>

#> # A tibble: 10 x 3

#> ncluster MSE `Std. Dev.`

#> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 1 51192. 4436.

#> 2 2 19170. 2996.

#> 3 3 14209. 4395.

#> 4 4 4572. 2905.

#> 5 5 4083. 2598.

#> 6 6 4048. 2540.

#> 7 7 3788. 2554.

#> 8 8 3696. 2603.

#> 9 9 3598. 2681.

#> 10 10 3500. 2689.A plot with error bars for one standard error, similar to the figure below, can be made from the output table using standard plotting functions to assist in assessing these results.

library(dplyr)

library(ggplot2)

ggcv(cp.table) +

geom_hline(aes(yintercept = min(lower1SD)), color = "red", linetype = 2) +

geom_hline(aes(yintercept = min(upper1SD)), color = "red", linetype = 2) +

geom_point(aes(x = ncluster[4], y = MSE[4]), color = "red", size = 2) +

geom_point(aes(x = ncluster[4], y = MSE[4]), color = "red", size = 5, shape = 4)

The choice of clusters for Ruspini data made by 10-fold CV where minCV selects 10 clusters and 1SE selects 4. The error bars are the \(\overline{MSE} \pm 1SE\) and the choice of 4 clusters, the simplest solution within 1 standard error of the minimum error estimate (the dashed lines coincide with the bar at 10 clusters) is highlighted with a \(\times\).

Another approach involves doing a formal hypothesis test at each split on the tree and using the \(p\)-values to decide on how many clusters should be used. This approach has been used in the context of conditional inference trees by Hothorn et al. (2006) although with a different test statistic and purpose. In that situation the test is used to test a null hypothesis of independence between the response and a selected predictor. For cluster analysis, at any cluster (or leaf on the decision tree), whether it will be partitioned or not is the result of a hypothesis test in which the pair of hypotheses can be abstractly stated as

\(H_0:\) The two new clusters are identical to each other, and

\(H_A:\) The two new clusters are different from each other.

To allow applications with any dissimilarity measure, a nonparametric method based on permutation is used. Anderson (2001) developed a multivariate nonparametric testing approach called perMANOVA that involves calculating the pseudo-\(F\)-ratio directly from any symmetric distance or dissimilarity matrix where the sum of squares are, in turn, calculated from the dissimilarities. The \(p\)-value can then be calculated by tracking the pseudo-\(F\) across permutations and comparing the results to the observed result and is available in the vegan package (Oksanen et al., 2019) in R. We considered two approaches for generating the permutation distribution under the previous null:

- Shuffle the observations between two proposed clusters. The pseudo-\(F\)’s calculated from the shuffles create the reference distribution to find the \(p\)-value. Because the splitting variable that was chosen is already the best in terms of reduction of inertia, that variable is withheld from the distance matrix used in the permutation test. This method can be done with

method = "sw"(default value) in theperm.testfunction. - Shuffle the values of the splitting variables while keeping other variables fixed to create a new data set, then the average silhouette width (Kaufman and Rousseeuw, 1990) is used as the measure of separation between the two new clusters and is calculated to create the reference distribution. Specifying

method = "rl"inperm.testwill run this method. - Similar to the previous method but pseudo-\(F\) (as in the first approach) is used as the test statistic instead of the average silhouette width. This approach corresponds to

method = "rn".

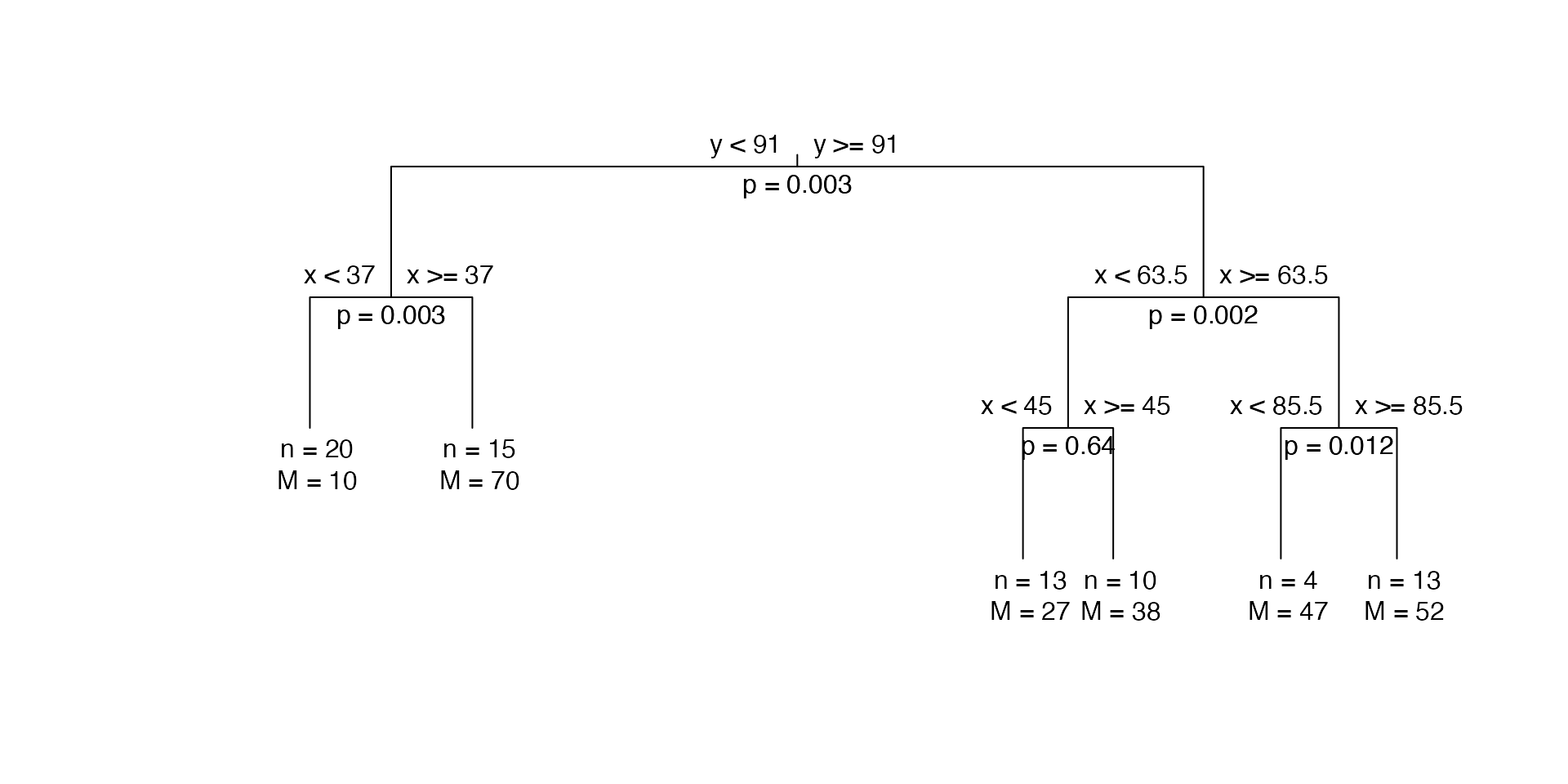

Applying the perm.test function to a MonoClust object will add permutation-based \(p\)-values to the output of both print and plot. Users can specify the number of permutations with the rep = argument. An example of applying the cluster shuffling approach to the ruspini data set follows and the tree output is in the figure below. Note that the Bonferroni-adjusted \(p\)-values are used to account for the multiple hypothesis tests required when going deeper into the tree. The number of tests for the adjustment is based on the number of tests previously performed to get to a candidate split and the maximum value of a \(p\)-value is always 1. A similar adjustment has been used in conditional inference trees and was also implemented in its accompanied party package (Hothorn et al., 2006).

ruspini6c <- MonoClust(ruspini, nclusters = 6)

ruspini6c.pvalue <- perm.test(ruspini6c, data = ruspini, method = "sw", rep = 1000)

plot(ruspini6c.pvalue, branch = 1, uniform = TRUE)

Binary partitioning tree with five splits, six clusters, but one split should be pruned based on its p-value of 0.8.

Clustering on Circular Data

In many applications, a variable can be measured in angles, indicating the directions of an object or event. Examples could be the times of day, aspects of the slope in mountainous terrain, directions of motion, or wind directions. Such variables are referred to as circular variables and are measured either in degrees or radians relative to a pre-chosen 0 degree position and meaning of a rotation direction. There are books dedicated to this topic (for example, Fisher, 1993; Jammalamadaka and SenGupta, 2001) that develop parametric models and analytic tools for circular variables. Here we demonstrate multivariate data analysis involving circular variables, such as visualization and clustering.

Cluster analysis depends on the choice of distance or dissimilarity between multivariate data points. A (dis)similarity measure that often comes up in the literature when dealing with mixed data types is Gower’s distance (Gower, 1971). It is a similarity measure among observations from various types of variables, such as quantitative, categorical, and binary, can be a reasonable alternative to Euclidean distance when working with “mixed” data.

Generally, the Gower’s dissimilarity in a simple form (without weights) for a data set with \(Q\) variables is \[d_{gow}(\mathbf{y_i},\mathbf{y_j}) = \frac{1}{Q} \sum_{q=1}^Q d_{gow}(y_{iq}, y_{jq}).\] If \(q\) is a linear quantitative variable, \[d(y_{iq}, y_{jq}) = \frac{|y_{iq} - y_{jq}|}{\max_{i,j}|y_{iq} - y_{jq}|}.\] It can also incorporate categorical variables, with \(d(y_{iq}, y_{jq})\) equals to 0 if the two observations belong to the same category of \(q\) and 1 otherwise. Details and examples can be seen in Everitt et al. (2011, Chapter 3). We extend the dissimilarity measure for a circular variable as \[d(y_{iq},y_{jq}) = \frac{180 - \left| 180 - |y_{iq} - y_{jq}| \right|}{180},\] where \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are the angles in degree. If radians are used, the constant 180 degrees will be replaced by \(\pi\). This distance can be mixed with other Gower’s distances both for monothetic clustering and in other distance-based clustering algorithms.

We demonstrated an application of monothetic clustering to a data set from Šabacká et al. (2012). This data set is a part of a study on microorganisms carried in föhn winds at the Taylor Valley, an ice free area in the Antarctic continent. The examined subset of the data is during July 7–14, 2008, at the Bonney Riegel location with three variables: the existence of particles measured in 1 minute every 15 minutes (binary variable of presence or absence), average wind speed (m/s), and wind direction (degrees) recorded at a nearby meteorological station every 15 minutes. Wind direction is a circular variable in which winds blowing from the north to the south were chosen to be 0/360 degrees and winds blowing from the east to the west were chosen to be 90 degrees. MonoClust works on circular data by indicating the index or name of the circular variable (if there is more than one circular variable, a vector of them can be transferred) in the cir.var argument.

data(wind_sensit_2008)

# For the sake of speed in the example

wind_reduced_2008 <- wind_sensit_2008[sample.int(nrow(wind_sensit_2008), 50), ]

sensit042008 <- MonoClust(wind_reduced_2008, nclusters = 4, cir.var = 3)

#> Warning in cluster::daisy(toclust[, -cir.var], metric = distmethod): binary

#> variable(s) 1 treated as interval scaledTo perform monothetic clustering, a variable must generate a binary split. Because of special circular characteristics, a circle needs two cuts to create two separate arcs instead of one cut-point as in conventional linear variables. Therefore, the algorithm to search for the best split in a circular variable is actually done in two folds; first by fixing one cut value and then searching for the second cut. This process is repeated by changing the first cut until all possible pairs of cuts have been examined and the best two cuts are then picked based on the inertia. The splitting rule tree is also updated to add the second split value on the corner of the tree. After the first split on a circular variable, the arcs can be considered as two conventional quantitative variables and can be split further with only a single cut-point. The figure above shows the resulting four clusters created by applying monothetic clustering on the Antarctic data.

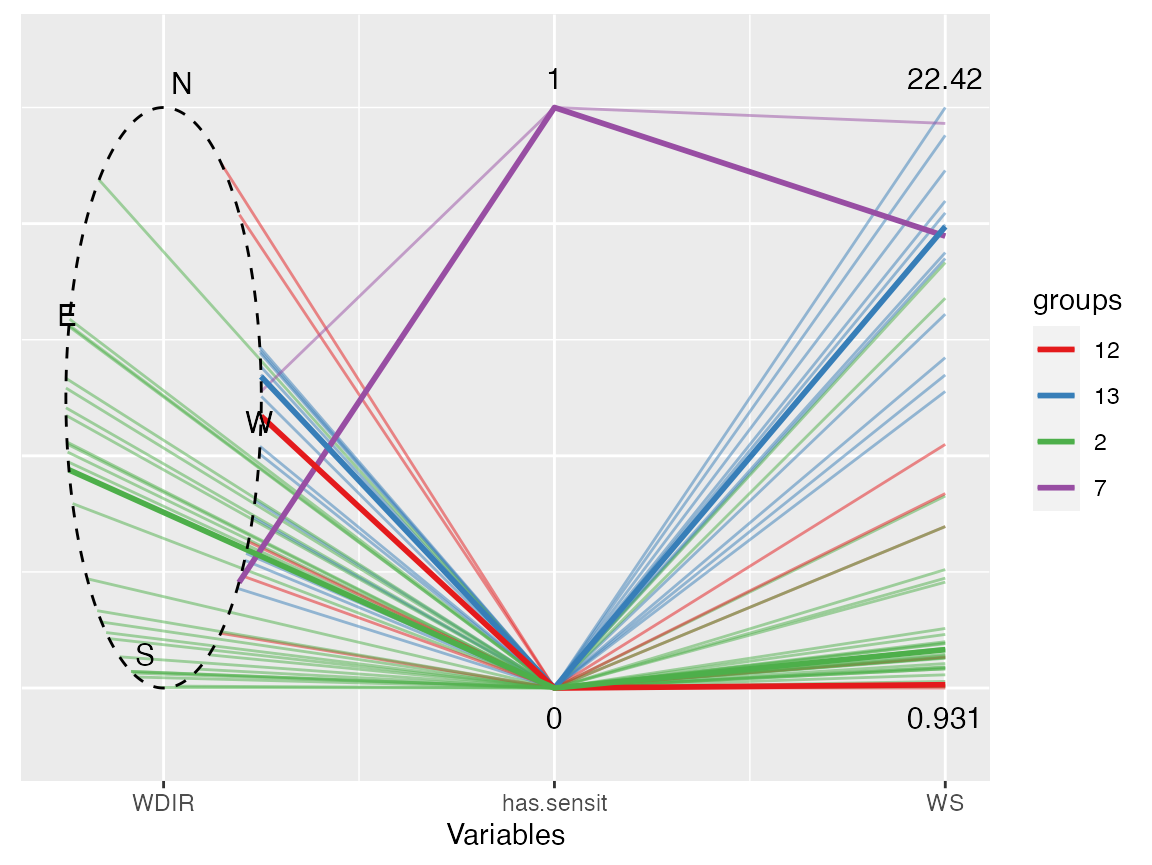

When clustering a data set that has at least one circular variable in it, visualizing the cluster results to detect the underlying characteristics of the clusters is very crucial. Scatterplots are not very helpful for circular data because of the characteristics of those variables. Dimension reduction can be performed using techniques like multi-dimensional scaling (Chapter 14, Hastie et al., 2016) or more recent techniques such as t-SNE (Hinton, 2008), but the details of the original variables are lost in these projections. Parallel Coordinates Plots (PCPs, Inselberg and Dimsdale, 1987), which can display the original values of all of the multivariate data by putting them on equally spaced vertical x-axes, are a good choice due to its simplicity and its capability to retain the proximity of the data points (Härdle and Simar, 2015, Chapter 1). A modified PCP, inspired by Will (2016), is also implemented in monoClust using ggplot2 (Wickham, 2016). The circular variable is displayed as an ellipse with the options to rotate and/or change the order of appearance of variables to help facilitate the detection of underlying properties of the clusters. The figure below is the PCP of the Antarctic data with the cluster memberships colored and matched to the tree in the figure above with the following codes. There are other display options that can be modified such as the transparency of lines, whether the circular variable is in degrees or radians, etc. (see the function documentation for details).

ggpcp(data = wind_reduced_2008,

circ.var = "WDIR",

rotate = pi / 4 + 0.6,

order.appear = c("WDIR", "has.sensit", "WS"),

clustering = sensit042008$membership,

medoids = sensit042008$medoids,

alpha = 0.5,

cluster.col = c("#e41a1c", "#377eb8", "#4daf4a", "#984ea3"),

show.medoids = TRUE)

PCP with the circular variable (WDIR) depicted as an ellipse. The geographical direction is noted and the ellipse is rotated to facilitate understanding of clusters.

Bibliography

- Anderson, M. J. (2001). “A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance”. In: Austral Ecology 26.1, pp. 32{46. issn: 14429985. doi:

10.1111/j.1442-9993.2001.01070.pp.x. - Breiman, L., J. Friedman, C. J. Stone, and R. Olshen (1984). Classification and Regression Trees. 1st ed. Chapman and Hall/CRC. isbn: 0412048418.

- Caliński, T. and J Harabasz (1974). “A dendrite method for cluster analysis”. en. In: Communications in Statistics 3.1, pp. 1-27.

- Charrad, M., N. Ghazzali, V. Boiteau, and A. Niknafs (2014). “NbClust: An R Package for Determining the”. In: Journal of Statistical Software 61.6.

- Chavent, M. (1998). “A monothetic clustering method”. In: Pattern Recognition Letters 19.11, pp. 989{996. issn: 01678655. doi:

10.1016/S0167-8655(98)00087-7. - Everitt, B. and T. Hothorn (2011). An Introduction to Applied Multivariate Analysis with R. 1st ed. Springer. isbn: 1441996494.

- Everitt, B. S., S. Landau, M. Leese, and D. Stahl (2011). Cluster Analysis. 5th ed. Wiley, p. 346. isbn: 0470749911.

- Fisher, N. I. (1993). Statistical Analysis of Circular Data. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. isbn: 9780511564345. doi:

10.1017/CBO9780511564345. - Gower, J. C. (1971). “A General Coefficient of Similarity and Some of Its Properties”. In: Biometrics 27.4, p. 857. issn: 0006341X. doi:

10.2307/2528823. - Härdle , W. K. and L. Simar (2015). Applied Multivariate Statistical Analysis. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. isbn: 978-3-662-45170-0. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-45171-7.

- Hardy, A. (1996). On the number of clusters". In: Computational Statistics & Data Analysis 23.1, pp. 83{96. issn: 0167-9473. doi:

10.1016/S0167-9473(96)00022-9. - Hastie, T., R. Tibshirani, and J. Friedman (2016). The Elements of Statistical Learning. 2nd ed. Springer. isbn: 978-0387848570.

- Hinton, G. (2008). “Visualizing Data using t-SNE”. In: Journal of Machine Learning Research 9.Nov, pp. 2579{2605. issn: 02545330. doi:

10.1007/s10479-011-0841-3. - Hothorn, T., K. Hornik, and A. Zeileis (2006). “Unbiased Recursive Partitioning: A Conditional Inference Framework”. en. In: Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics 15.3, pp. 651–674. issn: 1061-8600. doi:

10.1198/106186006X133933.33 - Inselberg, A. and B. Dimsdale (1987). “Parallel Coordinates for Visualizing Multi-Dimensional Geometry”. In: Computer Graphics 1987. Tokyo: Springer Japan, pp. 25{44. doi:

10.1007/978-4-431-68057-4_3. - James, G., D. Witten, T. Hastie, and R. Tibshirani (2013). An Introduction to Statistical Learning: with Applications in R. 1st. Springer, p. 426. isbn: 1461471370.

- Jammalamadaka, S. R. and A. SenGupta (2001). Topics in Circular Statistics. Vol. 5. isbn: 9789812779267. doi:

10.1142/9789812779267. - Kaufman, L. and P. J. Rousseeuw (1990). Finding Groups in Data: An Introduction to Cluster Analysis. 1st ed. Wiley-Interscience, p. 368. isbn: 978-0471735786.

- MacNaughton-Smith, P., W. T. Williams, M. B. Dale, and L. G. Mockett (1964). “Dissimilarity Analysis: a new Technique of Hierarchical Sub-division”. In: Nature 202.4936, pp. 1034{1035. issn: 0028-0836. doi:

10.1038/2021034a0. - MacQueen, J. (1967). Some methods for classification and analysis of multivariate observations. Berkeley, Calif.

- Maechler, M., P. Rousseeuw, A. Struyf, M. Hubert, and K. Hornik (2018). cluster: Cluster Analysis Basics and Extensions. R package version 2.0.7-1 — For new features, see the ‘Changelog’ file (in the package source).

- Milligan, G. W. and M. C. Cooper (1985). “An examination of procedures for determining the number of clusters in a data set”. In: Psychometrika 50.2, pp. 159–179. issn: 0033-3123. doi:

10.1007/BF02294245. - Murtagh, F. and P. Legendre (2014). “Ward’s Hierarchical Agglomerative Clustering Method: Which Algorithms Implement Ward’s Criterion?” In: Journal of Classification 31.3, pp. 274–295. issn: 0176-4268. doi:

10.1007/s00357-014-9161-z.34 - Piccarreta, R. and F. C. Billari (2007). “Clustering work and family trajectories by using a divisive algorithm”. In: Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society) 170.4, pp. 1061–1078. issn: 0964-1998. doi:

10.1111/j.1467-985X.2007.00495.x. - R Core Team (2020). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria. url: https://www.R-project.org/.

- Rousseeuw, P. J. (1987). “Silhouettes: A graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis”. In: Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics 20, pp. 53–65. issn: 03770427. doi:

10.1016/0377-0427(87)90125-7. - Ruspini, E. H. (1970). “Numerical methods for fuzzy clustering”. In: Information Sciences 2.3, pp. 319–350. issn: 00200255. doi:

10.1016/S0020-0255(70)80056-1. - Šabacká, M., J. C. Priscu, H. J. Basagic, A. G. Fountain, D. H. Wall, R. A. Virginia, and M. C. Greenwood (2012). “Aeolian ux of biotic and abiotic material in Taylor Valley, Antarctica”. In: Geomorphology 155-156, pp. 102–111. issn: 0169555X. doi:

10.1016/j.geomorph.2011.12.009.35 - Sneath, P. H. A. and R. R. Sokal (1973). Numerical taxonomy: the principles and practice of numerical classification. W.H. Freeman, p. 573. isbn: 0716706970.

- Therneau, T. and B. Atkinson (2018). rpart: Recursive Partitioning and Regression Trees. R package version 4.1-13.

- Ward, J. H. (1963). “Hierarchical Grouping to Optimize an Objective Function”. In: Journal of the American Statistical Association 58.301, pp. 236–244. issn: 0162-1459. doi:

10.1080/01621459.1963.10500845. - Wickham, H. (2016). ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer-Verlag New York. isbn: 978-3-319-24277-4. url: https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org.

- Will, G. (2016). “Visualizing and Clustering Data that Includes Circular Variables”. Writing Project. Montana State University.